Ryohei Yamashita†

Department of Bio resources and Environmental Sciences, Ishikawa Prefectural University, Nonoichi Japan

Abstract

Japan's rural areas are known for their natural environments being a source of ecosystem services. Today, the management and utilization of natural resources are important themes for the sustainability of rural areas in Japan. And, since population decrease and aging are simultaneously advancing in the rural area, the contribution of the neighboring urban area residents is indispensable. However, empirical studies on how the value of ecosystem services is understood by urban residents and contributes to their intentions in rural development strategies that promote regional vitality by encouraging their behavior change, such as participation in community activities and the purchase of traditional products, are insufficient. This study investigated the influence of public awareness on the hypothesis that ecosystem services are of public benefit value on investment related indirect conservation activities. The contingent valuation method was employed to estimate the willingness to pay (WTP) of citizens against the results of regional revitalization activities in which special branding was used for local agricultural products and traditional recipes. A full model analysis of the determinants of WTP was conducted. Revitalization plans for rural areas involving specially branded Japanese pickled vegetables offered ~40% added value compared to that of ordinary commodity foods. However, the tendency to regard ecosystem services as a provider of public benefits was not a significant factor influencing participation in conservation efforts; the two were not correlated. That is, general value recognition of ecosystem services in the agricultural mountain village region and concrete value recognition as a consumption object were not linked.

Keywords

Ecosystem services, Public benefit value, Consumer behavior, Contingent valuation method

1 Introduction

How to increase the number of individuals and groups contributing to natural resource management is an issue in many rural areas in Japan. Therefore, it is important to increase the momentum of spontaneous environmental conservation movements. Spontaneous actions require consensus that ecosystem services and the traditional culture of rural areas are “public benefit values,” which must be protected. Regarding the link between general value recognition for these ecosystem services and value recognition as a consumption object, not only academic interest but also practical needs from policymakers and regions aiming at regional activation are high.

A marketing strategy based on stakeholder perceptions and evaluations of goods (ecosystem services) is essential to the above scheme (Collis, David J. and Montgomery, C. A. 1997). This study analyzed consumer behavior to determine whether empathy for ecosystem services and the importance of traditional culture can result in changes in consumer consciousness based on the contingent valuation method (CVM). In particular, a sense of “public benefit” is used as a key concept in this analysis and is expected to lead to spontaneous participation in the conservation of the natural environment. If this study can attribute the environment related behavior of urban inhabitants to their cognition to values of the “public benefit” of ecosystem services, the results will be important for regional planning and environmental management.

A local project in a rural area in Japan was used as a case study to explore how the socio ecological system of a mountainous area could be revitalized. The local revitalization project studied in this analysis is the Kinameri settlement in Hakusan City, Ishikawa Prefecture (K--project). The study site produces high--quality vegetables, such as carrots and Japanese radishes; therefore, residents decided to launch a signature agricultural product made from products harvested in this area: additive--free Japanese pickled vegetables (JPVs) produced via traditional methods from agricultural products grown locally. Money earned from the JPVs was assumed to contribute toward the conservation of the natural environment. The main purpose of the study is to evaluate consumer consciousness for this particular case.

2 Research framework

2.1 Data collection

The questionnaire for CVM was distributed to the residents of Nonoichi City, which is contiguous with Hakusan City, Ishikawa prefecture, Japan. The important characteristics of the K--project are the establishment of manufacturing sites and the subsequent sale of JPVs and other specialty agricultural products in a farmer’s market.

The questionnaire was used to quantitatively analyze respondents’ attributes, experiences, and the influence that their view on natural resource benefits has on consumer behavior. Hence, the questionnaire focused on the following key determining factors: site, quality, and price. The key indicators used to characterize urban residents were age, the use of and excursions to a natural environment, subjective awareness of natural resources as public benefits, and the intention to visit a farmer’s market in the Kinameri settlement (K--settlement). In addition to the offer price used for the analysis, goods, for which these factors were combined at random, were described on the questionnaire sheet, and the data were then compared with the data of the other goods to evaluate consumer preferences. 1365 questionnaires were distributed and 917 were completed. The overall completion rate was 67%.

First, the “site” was assessed, based on a comparison of the typical supermarket visited by residents and the farmer’s market that was to be set up in the K--settlement. Next, an objective indicator was used to assess the “quality” (i.e., a product containing standard preservatives commonly seen in JPVs in the market and natural products without preservatives were compared). For the “price” factor, a standard price of \200/200 g was used, which was based on the results of the market survey conducted near the target area. Finally, the amount that the consumers were willing to pay for JPVs considering the previously discussed determining factors was calculated using the double--bounded dichotomous--choice CVM.

2.2 Analytical procedure

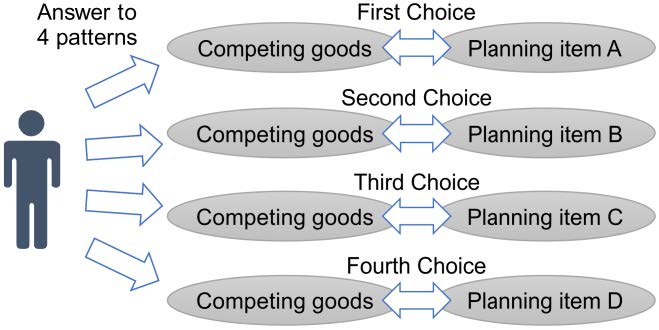

Four JPVs with different characteristics, including price, material, and the manufacturing method, were presented as alternatives to similar goods in the study. Each respondent chose JPVs four times in response to different questions (Fig. 1).

The questions included in the survey, to understand the personal attributes and characteristics of consumption behavior, and a summary of the statistics of the survey results, are shown in Table 1. The questionnaires where respondents selected response 3): “Do not want to visit at all” to Question 8 were excluded. Based on responses to the first question regarding preferences (see Fig. 2), the proposed price was increased or decreased. The double--bound dichotomous--choice method was adopted to estimate the WTP based on the responses to different proposed prices (described in Table 2 concisely).

Samples lacking one or more answers to the questions and those with option 3 selected for Question 8 were classified as protest responses. There were 109 protest responses, which were excluded from the analysis (exclusion rate = 109/917 or ~12%). The distributions based on the type of sense of public benefit (TSPB) determined using Questions 5 and 6 are shown immediately below the row containing Q6.

Table 2 presents the cross--tabulation of the answers to the questions used when calculating the WTP. As shown in Fig. 1, four different patterns were presented for each questionnaire, and the respondents were asked to choose one. “Yes” means that JPVs produced by the K--settlement were selected, whereas “No” means that competing goods were selected.

Figure 1: Flow of replies to four repeated questions

Table 1: Willingness to pay (WTP) influence factors and responses to each question

| No | Content of Items | Question Choices | Frequency | Remarks |

| Q1 | Generation |

1. Under 39 years old, 2. Those in their 40s, 3. Those in their 50s, 4. Those in their 60s, 5. Those above 70 years old. |

1. 134 2. 481 3. 460 4. 650 5. 820 |

Explanatory variables (personal attributes) |

| Q2 | Gender |

1. Male, 2. Female. |

1. 920 2. 716 |

Explanatory variables (personal attributes) |

| Q3 | Experience with natural environmental conservation activities |

1. Has experience, 2. Does not have experience. |

1. 980 2. 710 |

Explanatory variables |

| Q4 | Interest in participating in natural environmental conservation activities |

1. Would like to participate if there are opportunities, 2. Has no interest and would not like to participate. |

1. 351 2. 457 |

Explanatory variables |

| Q5 |

Subjective awareness of the scope of beneficiaries of ecosystem services in rural areas “Who is benefiting from it?” |

1. Only people who live in the area, 2. People and companies located within the area and in neighboring urban areas, 3. People living within the prefecture, 4. All people across a vast region (nation) or beneficiaries are unlimited |

1. 199 2. 990 3. 496 4. 140 |

Explanatory variables |

| Q6 |

Subjective awareness of the scope of the burden of managing the natural environment in rural areas “Who is responsible for environmental conservation?” |

1. Only people living in the area and public officials there, 2. People and companies located within the area and in neighboring urban areas; 3. People living within the prefecture, 4. All people across a vast region (nation) or there is no limit to who is responsible for conservation. |

1. 630 2. 630 3. 327 4. 355 |

Explanatory variables |

| Type of sense of public benefit (TSPB) |

1. Public benefit-oriented type 2. Neutral type 3. Free-rider type |

1. 456 2. 325 3. 370 |

determined using Q 5 and Q 6 |

|

| Q7 | Subjective awareness of the differences between benefits from urban convenience and ecosystem services from the natural environment |

1. Cannot distinguish and may complement each other, 2. Don’t know (cannot decide own opinion), 3. Can distinguish and understand each unique value. |

1. 287 2. 310 3. 211 |

Explanatory variables |

| Q8 | Intention to visit if a farmer’s market is established by the K-project |

1. Would definitely like to visit, 2. Don’t particularly want to visit, 3. Do not want to visit at all, 4. Don’t know (cannot decide own opinion). |

1.291 2.132 3.excluded 4.385 |

Identifying and excluding biased responses |

Table 2: Willingness to pay (WTP) influence factors and responses to each question

| First proposal | Yes/No | Second proposal | Yes/No |

| Case 1 ¥260 | 520/562 | ¥300 | 362/158 |

| ¥220 | 168/349 | ||

| Case 2 ¥320 | 297/511 | ¥360 | 213/84 |

| ¥280 | 159/352 | ||

| Case 3 ¥380 | 148/440 | ¥420 | 79/69 |

| ¥340 | 41/399 | ||

| Case 4 ¥440 | 57/642 | ¥480 | 111/46 |

| ¥400 | 51/591 |

3 Analysis and discussion

The results of the analysis are presented, as follows: The median of the WTP was ¥279, the average value with a cut-off at the maximum presented price was ¥292, and a price premium of ~40% was evaluated compared with that of the comparative product, which was assumed to be /200 (Table 3). The results showed that the strategy of the K-project is likely to be successful because a price premium can be expected from consumers.

The factors contributing to the acceptance of the proposed amounts were identified using the responses to Q1 to Q7 in Table 1 and the product attributes of the planned items as explanatory variables (Table 4). The aim was to determine whether the TSPB calculated from Q6 affected the acceptance probability. If some explanatory variables are significant, the TSPB can be used to encourage citizens to contribute to the conservation of the natural environment by strengthening actions that do not require substantial amounts of additional investment, such as environmental education. However, if not, the conservation of the natural environment and the awareness of the related public benefits are unrelated. In this case, the results of the statistical analysis did not indicate the effect of stimulating public value recognition for ecosystem services to promote participation in voluntary environmental conservation activities. That is, our results cannot support the hypothesis of this research and suggest that a certain degree of public funding is essential for the conservation of natural resources and communities in rural areas.

The evaluation of determinants derived from the full model analysis is shown in Table 4. The contribution of individual factors is interpreted, as follows: The acceptance probability of the proposed price increases as the age range (generation; X1) increases, and if the gender (X2) is female. By comparing these coefficients, we found that gender has a significant effect on the responses. Furthermore, the probability of acceptance of the proposed price is high when consumers have participated in conservation activities related to the natural environment (X3) and if they have a strong interest in the natural environment (X4). Similarly, by comparing these coefficients, we found that the presence or absence of such interest has a large influence on the responses. However, the influence of establishing a farmer’s market that reused idle facilities as a place to sell products and the sale of additive-free JPVs was not significant. In addition, the results suggest that the target audience should include elderly women with an interest in environmental conservation activities.

The influence of TSPB (X5) on the probability of acceptance was also analyzed, but it was not significantly affecting the probability of acceptance. However, people who can identify the difference between welfare due to the convenience of urban functions and welfare due to ecosystem services (X7), report a higher probability of acceptance. In other words, an understanding of this difference can encourage consumption as an indirect action leading to the conservation of ecosystem services. Therefore, the argument that it is possible to encourage voluntary conservation behavior via environmental education that informs people about the public benefit of ecosystem services is case-specific.

Table 3: Parameter estimation of function representing acceptance rate (P) for presented price

| Estimated WTP | Variable | Coefficient | t-value | p-value |

| ¥279 (Median) | Constant | 23.162 | 29.575 | 0.00** |

| ¥292 (Mean) | ln(bit) | −4.082 | −29.983 | 0.00** |

Note 1: n = 2160; Log-likelihood: −2,554.31; **: significance level of 1%, WTP denotes ‘willingness to pay’

Note 2: Mean value was cut off at the maximum presented price

Table 4: Variables used to estimate influential factors and correlation with willingness to pay

| Variable | Meaning | Coefficient | t-value | p-value |

| Constant | − | 21.809 | 31.600 | 0.00** |

| ln(bit) | − | −4.115 | −34.789 | 0.00** |

| X1 | Generation (~39 years:1, 40–49 years:2, 50–59 years:3, 60–69 years:4, 70 years ~:5) | 0.350 | 11.126 | 0.00** |

| X2 | Gender (Male: 1, Female: 0) | −0.769 | −6.514 | 0.00** |

| X3 | Experience of natural environment conservation activities (Has experience: 1, Does not have experience: 0) | 0.288 | 2.990 | 0.00** |

| X4 | Interest in participating in natural environment conservation activities (Has interest: 1, Does not have interest: 0) | 0.648 | 8.997 | 0.00** |

| X5 | Type of sense of public benefit (TSPB) | 0.141 | 1.959 | 0.05 |

| X6 | Subjective awareness of differences between benefits from urban convenience and ecosystem services from the natural environment (Cannot distinguish: 1, Cannot form an opinion: 2, Can distinguish: 3) | 0.236 | 3.225 | 0.00** |

| X7 | Selling place premium (At farmers’ market: 1, At daily supermarket similar to competing goods: 0) | 0.053 | 1.161 | 0.25 |

| X8 | Quality premium of product (Additive free: 1, With additives: 0) | −0.093 | −1.291 | 0.20 |

Note 1:n = 3232; Log-likelihood: −3,569.66; **: significance level of 1%.

Note 2: “Ordinal” denotes ordinal variable; “Dummy” denotes dummy variable.

Note 3:Regarding TSPB, as shown in Table 1, since the proportion of free riders was extremely small, options 2 and 3 were merged and replaced with dummy variables showing whether they correspond to a certain TSPB.

4 Conclusion

The natural environment and the traditional culture in rural areas, are recognized to offer certain benefits for citizens residing near urban areas. However, the relationship between a citizen’s awareness of ecosystem services as a public benefit and their participation in conservation activities is not supported by the results of this study.

The finding that the majority of citizens consider ecosystem services to offer a public benefit is helpful for the sustainable preservation of ecosystem services. However, the analysis of consumer behavior suggests that niche marketing is less effective for fostering public awareness and more effective for increasing product appeal regarding preservation of ecosystem services.

Acknowledgement

I would like to express my gratitude to the many people for responding to the survey. The study was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (grant numbers 18H03447, 15H 05630, 24780222).

References

- Collis, David J. and Montgomery, C. A. 1997. Corporate Strategy: A Resource-based Approach. Washington, DC: Richard D. Irwin, Inc.,.